Post by RedMoon11 on Mar 26, 2015 15:39:29 GMT

'Was Jeremy Clarkson trouble from the start? He sure was'

Former BBC Top Gear editor Tom Ross on how he gave the controversial presenter his first break – and whether the show can survive without the star

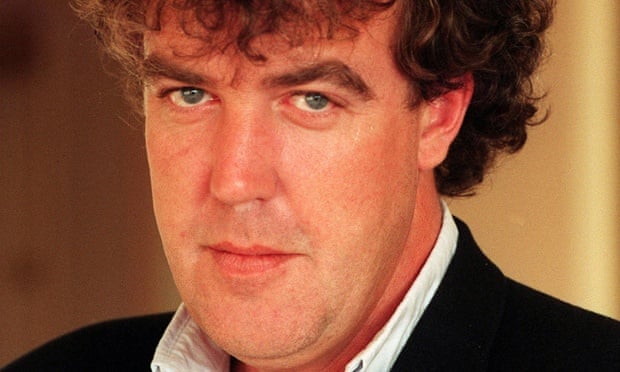

BBC Top Gear’s Jeremy Clarkson in the 1990s: ‘he always wanted to be a cross between Alan Whicker and Michael Parkinson’. Photograph: Peter Jordan/PA

Tom Ross

Thursday 26 March 2015 13.03 GMT

It is all my fault! Someone from the BBC has to step forward and take the blame for all the Clarkson headlines of the last few weeks and months. I am that person. Centuries ago in media terms I gave Jeremy Clarkson his break into television and first offered him the chance to be one of the presenters – albeit a junior one – on Top Gear. I certainly never expected Jeremy to become the worldwide phenomenon that he is today.

I should point out at the start that in 1987 – contrary to popular belief today – the original format of the programme already had more than 5 million viewers, and rising, and was often the top-rated show on BBC2. Those who say the show cannot survive without Jeremy conveniently forget that.

It had been a difficult ride. When I took over as executive producer in 1986 I was told by my local manager at the BBC’s studios at Pebble Mill in Birmingham that the show was on its last legs with six months to live. Things got even worse when Alan Yentob took over as controller of BBC2.

Programme producers were urged to make sweeping changes to the output with the inevitable danger of alienating loyal audiences. I preferred evolution to revolution: largely keeping the existing regular presenter line of William Woollard, Sue Baker and Chris Goffey. I also brought in specialists like Tiff Needell and rallying’s Tony Mason together with a new generation of younger reporters. Most importantly I encouraged female reporters to try to broaden the show’s audience appeal even further.

Top Gear always covered a broader range of motoring subjects but I wanted a harder journalistic edge and if possible a sense of fun. In the finest tradition of Boys from the Blackstuff Jeremy had playfully pestered my producers and me for a job at every car launch or motoring events on a regular basis. When we started looking for new faces my producer Jon Bentley, later a presenter of Channel 5’s Gadget Show, screen-tested half a dozen hopefuls and Jeremy stood out by a mile.

Was he trouble from the start? He sure was. In the early days I frequently took calls from the upper echelons of the British motor industry to complain about Jeremy’s comments on this road test or that. I easily silenced the critics by reminding them that I too had driven that particular car and that I agreed wholeheartedly with Jeremy’s assessment. The calls soon stopped and car companies realised that the old style of largely bland car tests had gone for ever.

My heart nearly stopped on one occasion when Jeremy came into my office and closed the door. The bad news was that on a car launch in Italy – nothing to do with Top Gear – he had an embarrassing moment involving other journalists. He did not know whether photographs existed.

I told him to say nothing and to hope none of his colleagues in the motoring press let him down. Happily they did not. As programme editor my superiors would, of course, have hung me out to dry if the facts had ever come out that I knew and did nothing. These were the days of a different kind of Producer Choice in the BBC.

In 1991 I moved on to other BBC pastures and eventually Jon Bentley took over the running of the programme. Unfortunately that coincided with a vacuum at the head of Pebble Mill and a new assertiveness from the bosses in London. Top Gear was now Jeremy’s show and by all accounts he began – not for the first time – to resent the indecisiveness and lack of direction at all levels in the BBC. He announced his retirement from the programme in 2001.

At a time when Pebble Mill was having output removed left right and centre, London took the decision to cancel the programme. The Birmingham-based staff were made redundant and Channel 5 commissioned a remarkably similar programme called Fifth Gear.

Jeremy went on to greater things with a string of excellent documentaries and a peculiar chatshow. He told me he always wanted to be a cross between Alan Whicker and Michael Parkinson. After a brief gap of a year the programme was reborn in the present format with Jeremy back, this time made in London and with his friend and former colleague Andy Wilman as executive producer. Richard Hammond joined the show and in the second series James May, who had not survived what became a regular cull of presenters by the original format programme in the late 1990s, was brought back. The rest is history.

The director general’s decision is a brave one but as Generation Game, Match of the Day, The One Show and other examples through the years prove the BBC, and a good show, can be bigger than any one star – however popular they are. But then I would say that, wouldn’t I?

Tom Ross was the editor of BBC Top Gear from 1986 to 1991

www.theguardian.com/media/2015/mar/26/jeremy-clarkson-bbc-top-gear

Former BBC Top Gear editor Tom Ross on how he gave the controversial presenter his first break – and whether the show can survive without the star

BBC Top Gear’s Jeremy Clarkson in the 1990s: ‘he always wanted to be a cross between Alan Whicker and Michael Parkinson’. Photograph: Peter Jordan/PA

Tom Ross

Thursday 26 March 2015 13.03 GMT

It is all my fault! Someone from the BBC has to step forward and take the blame for all the Clarkson headlines of the last few weeks and months. I am that person. Centuries ago in media terms I gave Jeremy Clarkson his break into television and first offered him the chance to be one of the presenters – albeit a junior one – on Top Gear. I certainly never expected Jeremy to become the worldwide phenomenon that he is today.

I should point out at the start that in 1987 – contrary to popular belief today – the original format of the programme already had more than 5 million viewers, and rising, and was often the top-rated show on BBC2. Those who say the show cannot survive without Jeremy conveniently forget that.

It had been a difficult ride. When I took over as executive producer in 1986 I was told by my local manager at the BBC’s studios at Pebble Mill in Birmingham that the show was on its last legs with six months to live. Things got even worse when Alan Yentob took over as controller of BBC2.

Programme producers were urged to make sweeping changes to the output with the inevitable danger of alienating loyal audiences. I preferred evolution to revolution: largely keeping the existing regular presenter line of William Woollard, Sue Baker and Chris Goffey. I also brought in specialists like Tiff Needell and rallying’s Tony Mason together with a new generation of younger reporters. Most importantly I encouraged female reporters to try to broaden the show’s audience appeal even further.

Top Gear always covered a broader range of motoring subjects but I wanted a harder journalistic edge and if possible a sense of fun. In the finest tradition of Boys from the Blackstuff Jeremy had playfully pestered my producers and me for a job at every car launch or motoring events on a regular basis. When we started looking for new faces my producer Jon Bentley, later a presenter of Channel 5’s Gadget Show, screen-tested half a dozen hopefuls and Jeremy stood out by a mile.

Was he trouble from the start? He sure was. In the early days I frequently took calls from the upper echelons of the British motor industry to complain about Jeremy’s comments on this road test or that. I easily silenced the critics by reminding them that I too had driven that particular car and that I agreed wholeheartedly with Jeremy’s assessment. The calls soon stopped and car companies realised that the old style of largely bland car tests had gone for ever.

My heart nearly stopped on one occasion when Jeremy came into my office and closed the door. The bad news was that on a car launch in Italy – nothing to do with Top Gear – he had an embarrassing moment involving other journalists. He did not know whether photographs existed.

I told him to say nothing and to hope none of his colleagues in the motoring press let him down. Happily they did not. As programme editor my superiors would, of course, have hung me out to dry if the facts had ever come out that I knew and did nothing. These were the days of a different kind of Producer Choice in the BBC.

In 1991 I moved on to other BBC pastures and eventually Jon Bentley took over the running of the programme. Unfortunately that coincided with a vacuum at the head of Pebble Mill and a new assertiveness from the bosses in London. Top Gear was now Jeremy’s show and by all accounts he began – not for the first time – to resent the indecisiveness and lack of direction at all levels in the BBC. He announced his retirement from the programme in 2001.

At a time when Pebble Mill was having output removed left right and centre, London took the decision to cancel the programme. The Birmingham-based staff were made redundant and Channel 5 commissioned a remarkably similar programme called Fifth Gear.

Jeremy went on to greater things with a string of excellent documentaries and a peculiar chatshow. He told me he always wanted to be a cross between Alan Whicker and Michael Parkinson. After a brief gap of a year the programme was reborn in the present format with Jeremy back, this time made in London and with his friend and former colleague Andy Wilman as executive producer. Richard Hammond joined the show and in the second series James May, who had not survived what became a regular cull of presenters by the original format programme in the late 1990s, was brought back. The rest is history.

The director general’s decision is a brave one but as Generation Game, Match of the Day, The One Show and other examples through the years prove the BBC, and a good show, can be bigger than any one star – however popular they are. But then I would say that, wouldn’t I?

Tom Ross was the editor of BBC Top Gear from 1986 to 1991

www.theguardian.com/media/2015/mar/26/jeremy-clarkson-bbc-top-gear