Post by RedMoon11 on Nov 19, 2013 11:15:10 GMT

White Van Man: Richard Hammond on Life Before Top Gear

At 21, Richard Hammond was a hard-up delivery driver, his dream of a radio career dying. But as he reveals in a new book, a trip to the Lake District with his van and his dog gave him fresh heart

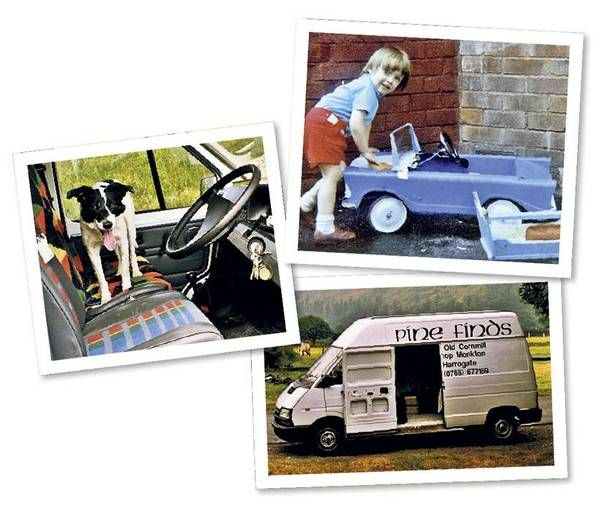

"A COMPANY van was, I had decided, a far better thing than a car. I was 21 and living in Ripon, North Yorkshire, working at a used furniture emporium called Pine Finds as salesman, polisher and occasional delivery man. I had tried to stay afloat on a freelance radio presenter’s income but it had proved too much and the new job came with a company van. And because the van was new I had to run it in; probably the first member of the Hammond family charged with running in a new vehicle in generations.

It was a handsome van, and sophisticated too. It was a Renault Trafic; about the size of the ubiquitous Ford Transit but lent, I believed, an altogether more interesting and cerebral air by its Gallic roots. Any muppet could pitch up in a Trannie full of buckets and hammers, but only someone with that little bit extra about them would roll up the gravel drive to your house in a Renault. And it was a high-top one too, the roofline extended upwards to accommodate the extra volume of the larger pieces of furniture I was called upon to deliver sometimes.

Today, though, my charge would be called into action for something special. Today my Renault Trafic would be elevated from a proud symbol of my blossoming career in antique pine trading, to become my home. I had planned a holiday, my first. I’d been on holiday before, but that was with my parents and they had always planned the trip, bought the provisions and booked the campsite.

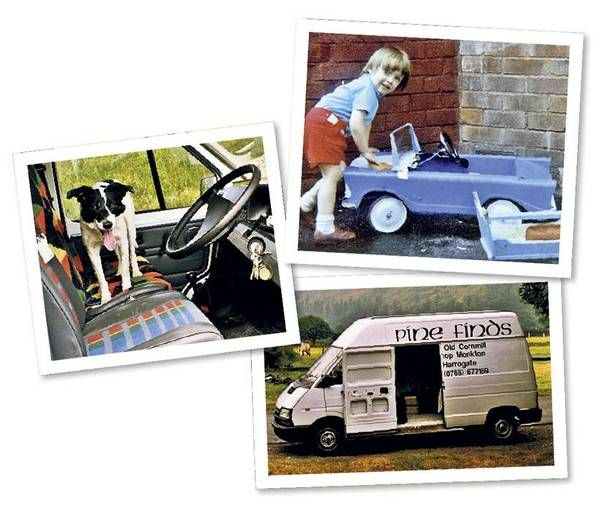

This time things would be different. I would be going on my own and take my van with me. Inside, I had set up accommodation, strapping an old armchair to the front bulkhead alongside the tea-chest into which I had stuffed everything essential to a young man holidaying for a week in Buttermere with his border collie.

Her metal food bowl sat on top of the pile of pans and plates and bags of socks crammed into the creaking tea-chest. Alongside the chest, tied to the wire mesh on the bulkhead, was my ancient green tent, there just in case the whole sleeping in the van thing didn’t work out.

I had no plans to indulge in challenging walks; the armchair was testimony to this. I would slide the big side door open and sit in the chair with my dog at my side, looking out at the hills and the little stream bordering the campsite on Sykes Farm. If I smoked a pipe, I would smoke one then. The idea nicely summed up my hopes for a relaxed, thoughtful, rather grown-up and gentlemanly holiday.

I had taken up with my dog, Abbey, several years ago in the planning stages of an ambitious walk around the coast of the UK. The walk was abandoned for reasons of finance and, if I’m honest, ambition, because I still hoped to turn my part-time radio work into something more full-time and felt that spending a year stomping along clifftops and beaches wouldn’t help me along in my media work. But Abbey had stayed with me and would love her holiday in the van.

Being a delivery driver was not an ambition of mine. I still held on to dreams of working as a radio or TV presenter, even though I had given up sporadic shifts as a freelance reporter at BBC local radio stations across the north in order to take the full-time job at the Pine Finds emporium in Bishop Monkton.

I had tried; God knows I’d tried to make it as a radio presenter. After losing my regular slot as programme assistant to the mid-morning show on BBC Radio York I had drifted into whatever radio work I could find, which meant living in bedsits and on sofas in towns and cities across the north, trying to hold down temporary contracts as reporter, programme assistant or producer. Leeds, Newcastle, Middlesbrough, Carlisle: a new radio station, another bedsit with brown-painted walls in a building haunted by unseen, noisy spectres in the next rooms, and another frightening newsroom full of earnest, committed journalists.

I got used to being the new boy, the guy from out of town, the one who didn’t really know the patch and who blushed on the few occasions he spoke up in a news meeting with some story he had gleaned from a newspaper and hoped no one else had seen. This exposure to different places would serve me well when I found work producing The Late Show, which was syndicated across northern local radio stations, but that wouldn’t be for another three years and right now I had to try to gain a foothold in adult life.

I was ill-prepared for a nomadic lifestyle. I craved roots, a place, a role; a slot in the world into which I could fit and where I could arrange my thoughts and plans and ideas. I don’t think this is unusual at 21: suddenly, all the guidance and help we’re offered through our childhood and into our teenage years dries up. We are finished, an adult, ready to go into the world — except we’re not. We don’t know how to spread our wings, but we’re too big for the nest.

The journey from child to adult is necessarily twisting and sometimes tricky. I had learnt that much. And looking back I understand that for me that journey ended after my 100-mile road trip from Ripon to Buttermere in the Lake District — my favourite place on earth.

My van had comfortable seats, quite high-backed; sporting, you might say. I did say so, and frequently, to my admiring friends. It had a radio-cassette player on which I would listen to tapes of JJ Cale, Frank Zappa and Howling Wolf, copied from my friends’ records.

It had a rev counter too, my van, and a 1.7-litre diesel engine: engines of such capacity were so far beyond the scope of young men like me as to be otherworldly, such was the grip that insurance companies held on the ambitions and hopes of young males dreaming of cars and power and all that they might do for our prospects and virility.

So we’re away on our holiday, my dog and I, and life is going well on board the good ship Renault up the A1. The clouds have thickened, changed from gauze to thick grey sludge, and it’s raining those big fat drops that spatter on the van’s screen, evenly spaced and round.

I grin and slot a cigarette between my lips, leaning forward over the wheel to let my forearms rest against it and dropping my head down to bring the cigarette in my mouth closer to the sparking lighter in my hand. “Well, girl,” I puff the words out through the side of my mouth in a cloud of blue smoke, “we’re on holiday now and nothing in the world can touch us.”

JJ Cale crooned to us about the wonders of city girls and their free-spirited ways, John Lee Hooker growled his appreciation of a woman’s way of walking about the place and Frank Zappa sang of a young biker’s wager with the devil over a girl’s breasts and some beer.

We were in high spirits, although the ship was swaying a bit. The Renault Trafic handles reasonably well, for a van, but the high roof makes it vulnerable to crosswinds and it can, when only lightly loaded, develop an alarming sway. We were lightly loaded and Abbey and I looked nervously at one another when the swaying grew more pronounced.

Fuel stop. Ease the joints, let the dog out for a pee on the grass by the car park and face the fact that I needed diesel. In the end, my debit card managed to cough up £10 without protest, though I doubted it would manage the feat too many more times.

The burden of young adulthood, with all its necessary financial complications and responsibilities, was not lying lightly on my 21-year-old shoulders. I had recently been thrown out of Barclays bank for some minor infringement or other of its rules pertaining to overdrafts and cheques. I didn’t really care about my account being closed, but it was the way the bank had done it that wounded.

The final blow had been delivered publicly, in the banking hall of its magnificent edifice in Ripon’s historic market square, when the clerk had demanded the immediate return of my chequebook and card. People had stared. I had blushed. And I was still cross with myself over how I handled it. I should have swaggered out, playing the rebel, maybe flicked a V-sign or told them to go screw themselves. Instead, I trickled out onto the street in a dribble of lower-middle-class shame, wondering how the hell people climbed out of the mire of miserable, cheque-bouncing brokeness in which I imagined I would be condemned to spend the rest of my life.

But it didn’t matter right now; I was in an almost brand-new company van, headed for my favourite place in the world with my dog, a new chequebook [from a new account] and the prospect of my first, independently organised, planned and paid-for holiday as an adult lying before me. Things were good.

We’re going west now on the A66. It’s a brooding, sombre stretch of black-and-white road permanently drenched and battered by Wuthering Heights weather. The road ahead clings stubbornly to hillsides and makes tight turns at the top of gaping, hungry chasms.

The names along the A66 sound old, time-served and proven, but somehow not friendly: Dalton, Forcett, Whorlton, Rokeby, Boldron, Reeth. It feels as if I am leaving the security and comfort of a county that, while not my birthplace, I can at least call home.

We swing south on the B5289, the Borrowdale road. I push the van as hard as I dare. I should slow down, take it in, relax; I’m on holiday. But I am excited and full of a young man’s energy. The noise, the thrill, the pace of it: I’m releasing this energy that otherwise would make me explode. The diesel engine moos and moans like an ill-tempered cow being prodded up the ramp into an abattoir truck.

“You OK, girl?” I breathe. Abbey looks up — she’s braced on the seat’s broad cloth, her legs must have worked hard to keep her from plunging down into the footwell. “Nearly there. Nearly there.” I smooth my hair back. It’s still long, almost down to my elbows, and I reach behind my head to gather it up, gripping it tightly in a sweating palm and pulling it back behind my shoulders.

I know all that waits ahead now is my favourite place on earth. Swinging around Seatoller, we begin the climb up to Honister Pass.

There’s a tipping point at the top, a final turn, a final crest and there is the Buttermere valley. My mind snapshots the last instant as we cross and it’s as though I can stand, frozen in time, balanced on tiptoe with arms outstretched like a diver on the highest board.

In an instantaneous blur I consider everything that worries me, every nagging concern; maybe I’ll get the chance to work Quote 2.jpg back at the radio station, maybe it will turn into something more, something bigger, maybe I’ll succeed, maybe one day I’ll understand what success is and maybe my new bank account will hold out. A wife, children, a home of my own, respect, ambition — all of these things and more I gather up and tuck under a rock, just one of millions up here at the pass, before I begin the long, lazy swoop down to the valley."

© Richard Hammond 2013

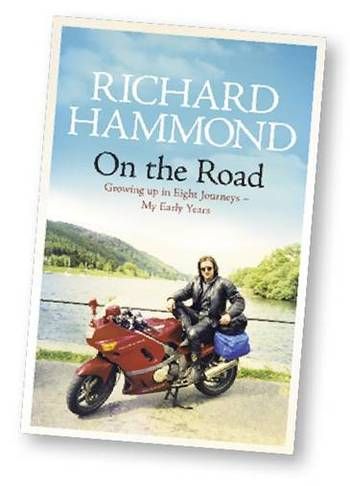

This is an edited extract from On the Road (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £18.99 in hardback and £9.49 as an ebook).

www.driving.co.uk/features/white-van-man-richard-hammond-on-life-before-top-gear/16387

At 21, Richard Hammond was a hard-up delivery driver, his dream of a radio career dying. But as he reveals in a new book, a trip to the Lake District with his van and his dog gave him fresh heart

"A COMPANY van was, I had decided, a far better thing than a car. I was 21 and living in Ripon, North Yorkshire, working at a used furniture emporium called Pine Finds as salesman, polisher and occasional delivery man. I had tried to stay afloat on a freelance radio presenter’s income but it had proved too much and the new job came with a company van. And because the van was new I had to run it in; probably the first member of the Hammond family charged with running in a new vehicle in generations.

It was a handsome van, and sophisticated too. It was a Renault Trafic; about the size of the ubiquitous Ford Transit but lent, I believed, an altogether more interesting and cerebral air by its Gallic roots. Any muppet could pitch up in a Trannie full of buckets and hammers, but only someone with that little bit extra about them would roll up the gravel drive to your house in a Renault. And it was a high-top one too, the roofline extended upwards to accommodate the extra volume of the larger pieces of furniture I was called upon to deliver sometimes.

Today, though, my charge would be called into action for something special. Today my Renault Trafic would be elevated from a proud symbol of my blossoming career in antique pine trading, to become my home. I had planned a holiday, my first. I’d been on holiday before, but that was with my parents and they had always planned the trip, bought the provisions and booked the campsite.

This time things would be different. I would be going on my own and take my van with me. Inside, I had set up accommodation, strapping an old armchair to the front bulkhead alongside the tea-chest into which I had stuffed everything essential to a young man holidaying for a week in Buttermere with his border collie.

Her metal food bowl sat on top of the pile of pans and plates and bags of socks crammed into the creaking tea-chest. Alongside the chest, tied to the wire mesh on the bulkhead, was my ancient green tent, there just in case the whole sleeping in the van thing didn’t work out.

I had no plans to indulge in challenging walks; the armchair was testimony to this. I would slide the big side door open and sit in the chair with my dog at my side, looking out at the hills and the little stream bordering the campsite on Sykes Farm. If I smoked a pipe, I would smoke one then. The idea nicely summed up my hopes for a relaxed, thoughtful, rather grown-up and gentlemanly holiday.

I had taken up with my dog, Abbey, several years ago in the planning stages of an ambitious walk around the coast of the UK. The walk was abandoned for reasons of finance and, if I’m honest, ambition, because I still hoped to turn my part-time radio work into something more full-time and felt that spending a year stomping along clifftops and beaches wouldn’t help me along in my media work. But Abbey had stayed with me and would love her holiday in the van.

Being a delivery driver was not an ambition of mine. I still held on to dreams of working as a radio or TV presenter, even though I had given up sporadic shifts as a freelance reporter at BBC local radio stations across the north in order to take the full-time job at the Pine Finds emporium in Bishop Monkton.

I had tried; God knows I’d tried to make it as a radio presenter. After losing my regular slot as programme assistant to the mid-morning show on BBC Radio York I had drifted into whatever radio work I could find, which meant living in bedsits and on sofas in towns and cities across the north, trying to hold down temporary contracts as reporter, programme assistant or producer. Leeds, Newcastle, Middlesbrough, Carlisle: a new radio station, another bedsit with brown-painted walls in a building haunted by unseen, noisy spectres in the next rooms, and another frightening newsroom full of earnest, committed journalists.

I got used to being the new boy, the guy from out of town, the one who didn’t really know the patch and who blushed on the few occasions he spoke up in a news meeting with some story he had gleaned from a newspaper and hoped no one else had seen. This exposure to different places would serve me well when I found work producing The Late Show, which was syndicated across northern local radio stations, but that wouldn’t be for another three years and right now I had to try to gain a foothold in adult life.

I was ill-prepared for a nomadic lifestyle. I craved roots, a place, a role; a slot in the world into which I could fit and where I could arrange my thoughts and plans and ideas. I don’t think this is unusual at 21: suddenly, all the guidance and help we’re offered through our childhood and into our teenage years dries up. We are finished, an adult, ready to go into the world — except we’re not. We don’t know how to spread our wings, but we’re too big for the nest.

The journey from child to adult is necessarily twisting and sometimes tricky. I had learnt that much. And looking back I understand that for me that journey ended after my 100-mile road trip from Ripon to Buttermere in the Lake District — my favourite place on earth.

My van had comfortable seats, quite high-backed; sporting, you might say. I did say so, and frequently, to my admiring friends. It had a radio-cassette player on which I would listen to tapes of JJ Cale, Frank Zappa and Howling Wolf, copied from my friends’ records.

It had a rev counter too, my van, and a 1.7-litre diesel engine: engines of such capacity were so far beyond the scope of young men like me as to be otherworldly, such was the grip that insurance companies held on the ambitions and hopes of young males dreaming of cars and power and all that they might do for our prospects and virility.

So we’re away on our holiday, my dog and I, and life is going well on board the good ship Renault up the A1. The clouds have thickened, changed from gauze to thick grey sludge, and it’s raining those big fat drops that spatter on the van’s screen, evenly spaced and round.

I grin and slot a cigarette between my lips, leaning forward over the wheel to let my forearms rest against it and dropping my head down to bring the cigarette in my mouth closer to the sparking lighter in my hand. “Well, girl,” I puff the words out through the side of my mouth in a cloud of blue smoke, “we’re on holiday now and nothing in the world can touch us.”

JJ Cale crooned to us about the wonders of city girls and their free-spirited ways, John Lee Hooker growled his appreciation of a woman’s way of walking about the place and Frank Zappa sang of a young biker’s wager with the devil over a girl’s breasts and some beer.

We were in high spirits, although the ship was swaying a bit. The Renault Trafic handles reasonably well, for a van, but the high roof makes it vulnerable to crosswinds and it can, when only lightly loaded, develop an alarming sway. We were lightly loaded and Abbey and I looked nervously at one another when the swaying grew more pronounced.

Fuel stop. Ease the joints, let the dog out for a pee on the grass by the car park and face the fact that I needed diesel. In the end, my debit card managed to cough up £10 without protest, though I doubted it would manage the feat too many more times.

The burden of young adulthood, with all its necessary financial complications and responsibilities, was not lying lightly on my 21-year-old shoulders. I had recently been thrown out of Barclays bank for some minor infringement or other of its rules pertaining to overdrafts and cheques. I didn’t really care about my account being closed, but it was the way the bank had done it that wounded.

The final blow had been delivered publicly, in the banking hall of its magnificent edifice in Ripon’s historic market square, when the clerk had demanded the immediate return of my chequebook and card. People had stared. I had blushed. And I was still cross with myself over how I handled it. I should have swaggered out, playing the rebel, maybe flicked a V-sign or told them to go screw themselves. Instead, I trickled out onto the street in a dribble of lower-middle-class shame, wondering how the hell people climbed out of the mire of miserable, cheque-bouncing brokeness in which I imagined I would be condemned to spend the rest of my life.

But it didn’t matter right now; I was in an almost brand-new company van, headed for my favourite place in the world with my dog, a new chequebook [from a new account] and the prospect of my first, independently organised, planned and paid-for holiday as an adult lying before me. Things were good.

We’re going west now on the A66. It’s a brooding, sombre stretch of black-and-white road permanently drenched and battered by Wuthering Heights weather. The road ahead clings stubbornly to hillsides and makes tight turns at the top of gaping, hungry chasms.

The names along the A66 sound old, time-served and proven, but somehow not friendly: Dalton, Forcett, Whorlton, Rokeby, Boldron, Reeth. It feels as if I am leaving the security and comfort of a county that, while not my birthplace, I can at least call home.

We swing south on the B5289, the Borrowdale road. I push the van as hard as I dare. I should slow down, take it in, relax; I’m on holiday. But I am excited and full of a young man’s energy. The noise, the thrill, the pace of it: I’m releasing this energy that otherwise would make me explode. The diesel engine moos and moans like an ill-tempered cow being prodded up the ramp into an abattoir truck.

“You OK, girl?” I breathe. Abbey looks up — she’s braced on the seat’s broad cloth, her legs must have worked hard to keep her from plunging down into the footwell. “Nearly there. Nearly there.” I smooth my hair back. It’s still long, almost down to my elbows, and I reach behind my head to gather it up, gripping it tightly in a sweating palm and pulling it back behind my shoulders.

I know all that waits ahead now is my favourite place on earth. Swinging around Seatoller, we begin the climb up to Honister Pass.

There’s a tipping point at the top, a final turn, a final crest and there is the Buttermere valley. My mind snapshots the last instant as we cross and it’s as though I can stand, frozen in time, balanced on tiptoe with arms outstretched like a diver on the highest board.

In an instantaneous blur I consider everything that worries me, every nagging concern; maybe I’ll get the chance to work Quote 2.jpg back at the radio station, maybe it will turn into something more, something bigger, maybe I’ll succeed, maybe one day I’ll understand what success is and maybe my new bank account will hold out. A wife, children, a home of my own, respect, ambition — all of these things and more I gather up and tuck under a rock, just one of millions up here at the pass, before I begin the long, lazy swoop down to the valley."

© Richard Hammond 2013

This is an edited extract from On the Road (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £18.99 in hardback and £9.49 as an ebook).

www.driving.co.uk/features/white-van-man-richard-hammond-on-life-before-top-gear/16387