|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 16:00:31 GMT

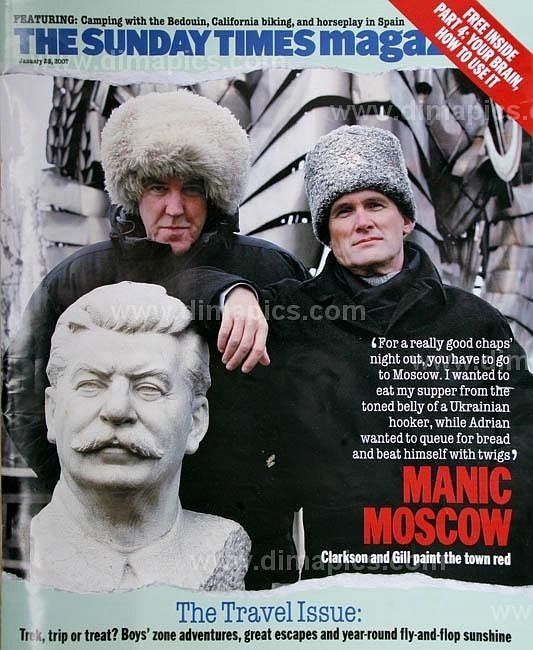

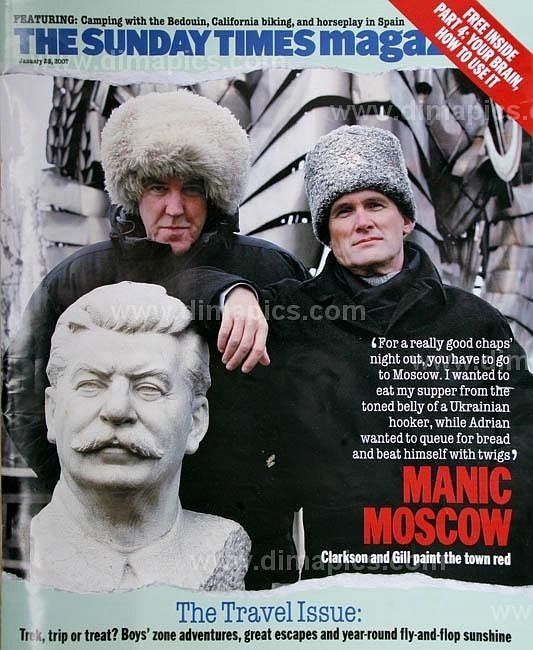

Jeremy Clarkson and A.A. Gill's Adventures -The Sunday Times Magazine Features

High Gays and HolidaysGill and Clarkson flew the pink-eye to the gay mecca of Mykonos, to get in touch with their feminine side. But they weren't the happiest of campers

AA Gill and Jeremy Clarkson Published: 22 December 2002  Let's get one thing straight. Jeremy Clarkson. Clarkson is very straight. He's so straight you could grow soft fruit up him. If you put oil in his bellybutton you could use him as a spirit level. There isn't a kink, a curve or a rococo gesture about him. Clarkson likes to define himself by what he's not. And what he's principally not is bent. He's so unbent that there are those who might say he was actively homophobic. But they'd be wrong. He's not homophobic in the way some are, say, arachnophobic. If Jeremy came across a homosexual in his bath, he wouldn't jump on the loo seat holding his nightshirt tightly at the knees and call in a desperate falsetto for his wife to come and deal with the huge, hairy thing. No, Jeremy feels about homosexuality rather what Neville Chamberlain felt about Czechoslovakia. A far and distant place of which he knows nothing; and, frankly, he doesn't care who buggers about with it, just as long as he's not expected to lend a hand. Though it must be said there is a sweaty whiff of the lower fourth about him. A touch of the schoolboy sniggers when it comes to queers. When we first planned this article, he wanted to take me to Norway for the World Powerboat Championship. Well, you can imagine: all Heineken, herring and handbrake turns. No, I said firmly, you really don't need to get in touch with more high-octane petrol heads and their interminable back problems. You need to get in touch with some sexuality. Not yours; yours is best left sleeping under its rock. You need to reach out for someone else's. And so it was. We landed on sunny Mykonos. My own relationship with homosexuality is perhaps no less irrational than Jeremy's for a heterosexual man. I love it. Having been brought up in a theatrical family, I spoke Polari (gay slang) as soon as I could speak English. I'm drawn to camp humour, bitchiness and gay culture. I feel at home with everything except their genitals. My hard-and-fast rule has always been one willy in bed at a time. 'You know what you are?' a gay friend told me. 'You're a stray - a straight gay man. But there's still time.' I haven't been to the Greek islands for a decade. Christ, make that two decades. But I have happy, sybaritic memories of them, and as we stepped off our little jet it all came back to me. The memories were despite the geography, rather than because of it. The Greek islands must have been made when God was going through his brief minimal, brutalist period. Mykonos is a sparse, crumbling camel-coloured lump. There are features, but none of them are interesting. The building material of choice, which the Greeks use with chaotic abandon, is concrete and breeze block. But then this is the only landscape on Earth where they look organic and harmonious. Despite being mentioned in the Odyssey and Herodotus and therefore possibly the oldest tourist destination in the world, Mykonos is principally famous for its very modern homosexuality. Since the 1960s it has been a mecca (probably not the right word) for young gays in search of a bit of the other, or rather, a bit of the same. Mykonos means 'island of wind', which you, like Jeremy, may find a sniggeringly funny joke for a gay resort. The first surprise is that not everyone is homosexual. I don't know exactly what we were expecting. La Cage aux Folles meets Gay Pride week, I suppose. But as well as being slippery heaven, Mykonos is also Hellenic St Tropez. Athenian families weekend here and pay monumental sums for whitewashed Portakabins and rock gardens. They do that paternal promenading thing of getting all dressed up and strolling purposelessly around town in the early evening. But whereas in Italy or Spain this would be a jolly occasion, a chance for young people to meet and possibly mate, here the families march in descending size, led by fathers who have the mien of minotaurs and glare at any male under 50. They're followed by daughters who sulk behind thick fringes, their eyes streaming from the fumes of their moustache peroxide. Mykonos is obviously a place for dressing up. Not fashionably. This is Greece, after all. But making an effort. And plainly, oh, you can't imagine how plainly, Jeremy needs some holiday clothes. I can't think where he thought he was going when he packed. A weekend's go-karting in Lincolnshire, perhaps? After an enormous amount of coaxing I manage to get him into a beach-front boutique run by a mere slip of a chap who immediately confirms all Clarkson's worst fears by asking him his star sign. Getting Jeremy to try anything on is more effort than getting Naomi Campbell to choose a wedding dress. Finding something he could try on is even harder. The small Asians who stitched this stuff can't have imagined anything his size outside of a Hindu temple. The waif-like shop boy regards his stomach the way a plumber regards a blocked septic tank. Then, with a little squeak, Clarkson dives into a corner and pulls out a pair of culottes. They fit. After a fashion. A long way after any known fashion. They are, without qualification or demur, the most appalling item of holiday clothing ever made. They can only have been designed for a bet. They're a patchwork of garish, oriental offcuts that look like a mental hospital's sewing bee's quilt turned into po'boy's clam-diggers. They come from the Waltons' cruiser-wear collection, and Clarkson adores them. He does little mewing pirouettes in front of the mirror. Out in the unforgiving sunlight, Jeremy saunters. I follow at an anonymous distance and watch as sensitive gay boys press themselves against walls to let this taste-apocalypse pass, just in case he's contagious. It's time to meet gay guys and they come out at night. Pierro's is, they say, the oldest and most popular gay disco bar in the Aegean. It's a two-storey town house, set on a tiny square. We arrive fashionably early. I've managed to convince Jeremy to leave the Tennessee troll kecks in his room. And he's relaxed and ready for a night on the town. Except he's not. He's about as relaxed as a greyhound in the soft-toy department of Hamleys. He sits stiffly on a bar stool, clutching a beer, imagining he's insouciantly invisible in the way only a 6ft 4in pubic-headed, Spacehopper-gutted, hulking heterosexual in mail-order chinos and docksiders can. After five minutes he hisses: 'Psst... I've been picked up.' Where, how, who, why? 'That man over there. Don't look.' He shrugs at a gaspingly beautiful olive-skinned, long-lashed 20-year-old Greek boy with black curls falling over his shoulders, and a thin singlet barely covering a body that would keep a girls' school dormitory panting for a fortnight. 'He fancies me.' No he doesn't. 'Yes he does.' No, he's having a thing with the transvestite barman who's standing behind you. 'How do you know?' I just know. Gaydar. Gaydar is a queer sixth sense. 'But you promised, swore you were straight.' I am. I just inherited gaydar from my mother's side, and anyway I saw them kissing two minutes ago. Jeremy is not convinced. The only thing he is convinced of is that every homosexual on the planet is yearning to do the love that dare not speak its name (unless you hit your thumb with a hammer) to him. This, you will have noticed, is a common delusion among stridently heterosexual men. What makes you think gay men want to worship at the temple of your body, Jeremy? 'Well, they do. It's obvious. They're homos. I'm a man. I'm virgin meat for them. It's well known that what homos really fancy are straight, married blokes. I thought you were supposed to know about these things.' Jeremy, let me say this with utter conviction. Trust me. Relax. Nobody here fancies you. Not on drugs, not for money, not remotely. Virginal and married as you are, you really aren't God's gift to gay men. You're not God's gift to straight women, either. In fact, you're not God's gift to anyone, except perhaps Colonel Sanders. The only thing that's remotely, attractively gay about you is your name. 'What, Jeremy?' No, Motormouth. (Page 1) The bar begins to fill up. By 2am it's a hog-throbbing, bouncy, smiley pick-up joint. Jeremy and I might as well be fire extinguishers. Apart from all the other stuff, we're just way too old. The age limit is severe. Young men between 18 and 30 who look like footballers. The street outside could be a Manchester United summer school. There are one or two overtly camp queens, but in general the desired effect is sporty and butch. On a balcony next door, three taut Hinge and Bracket trannies strike Dietrich poses. They look as coyly old-fashioned as black-and-white movies. I get caught in a corner by a nice Spanish architect who intensely explains the gay blitzkrieg theory of culture. Apparently, all culture is trailblazed by gay men. They're followed by straight women, who in turn attract straight men, who make the scene passe and mainstream, so the gays move on and invent something else. I nod and smile and apologise for being here and messing the place up. Jeremy has managed to find a pair of organically grown real women. They've just been married to each other in Vermont and are on their honeymoon. He gives me a wink. By four I'm exhausted by the relentless fitness and exuberance. I don't think I can stand another bump-and-grind conga in a miasma of Egoiste and Le Bleu. We walk back to our hotel through the wide-awake town. I pass on the gay theory of culture to Jeremy. 'Well, they didn't make any Ferraris or the Mustang or the Blackbird Stealth Interceptor, did they?' No, I don't think gay culture stretches to engineering. Though they might have done the Teasmade and the trouser press. 'Have you noticed anything strange about this place, apart from all the puffs?' he asks. 'There are no drunks. No vomit in the streets, no fights, no screaming gangs. If this were northern Europe, the place would be awash with blood, piss and sirens by now.' And it's true. A recent US study found that gays were the least violent and aggressive men on Earth (beating Tibetan monks on a technical knockout). There must be more muscle and testosterone in Mykonos tonight than in a season of rugby league. But there's no trouble. In fact, gay men as a demographic are more law-abiding than the rest of us. More civic-minded, socially concerned. They vote more, earn more, clean up more. They read more. Go to more theatres. Consume more. Have better jobs. Better health. Pay more taxes. And are better educated. In fact, gay men are model citizens. On paper we all should be aspiring to be gay men. By rights, logically, we should hope all our sons were gay. There's just that one little thing. 'It's not a little thing,' splutters Jeremy. 'It's a bloody big thing. A huge, hideous, humiliating, hurting thing. And I'd rather live on a sink estate in Cardiff and ride a bike without a saddle.' Next morning, Jeremy comes down for breakfast. So how did he enjoy his first gay nightclub? 'It was surprisingly good fun. Those two I was talking to.' The Velcro Sisters? 'Yes, the fuzz-bumpers. I was in there.' No you weren't. 'I was, I could have pulled.' Jeremy, they were lesbians, on their honeymoon. 'Exactly. What's a girl need on her honeymoon?' Oh, good grief. Today we're going to the beach. Now, how many beaches are advertised as being paradise? Plenty. All over the world, paradise is offered as standard. But here on Mykonos they've improved it. Here they've got Super Paradise. Super Paradise Beach is a long strand of grey gravel that swelters under an unrelenting sun. It's a bit like walking on the bottom of a goldfish bowl. At one end there's a bar that has a throbbing techno-house, garage, conservatory, granny-flat disco pumping continuously. The beach is gay-graded. It starts off as Greek hetero couples, drifts into international hetero singles, then Euro singles peeping out of the closet onto vanilla gays with fag hags, then very gay gays, and finally, up at the far end, very stern, serious, professional, alpha-male gays. Jeremy leads the way until we're sitting pressed up against the far cliff in the middle of a seal colony of vast, oily, naked, predatory homosexuals. You'll have to imagine this. These men don't just have honed, chiselled bodies; they have the sort of bodies that no sport, exercise or lifetime with Twyla Tharp can contrive. These muscles are solely for the purpose of display, and they are staggering. Entirely hairless and greased up to shine like a motor show. Every time they move, a new bit of body pops up. These guys are human advent calendars. The comparison with Jeremy's body is as astonishing as it is hilarious. It certainly seems to astonish the rest of the beach. Only David Attenborough could swear that Jeremy and the gay men were from the same species. Clarkson is Day-Glo white. Yorkshire white, with a tinge of blue. He looks like a collapsed wedding cake displayed in a mixed grill. The alpha gays don't do much except smoke and rearrange their muscles. Occasionally they saunter to the water until it laps their groins provocatively. Now, I haven't had the pleasure of a lot of willies all together since school. My, they've changed, and I must say I was astonished at the sheer variety. Pubic hair is not completely depilated. It's tonsured into amusing little penile moustaches, which seen together rather resemble a group photograph of pre-1914 Austrian hussars. The p3nis is the one muscle that really doesn't improve with exercise or working out. I mean, there are some organs here that are frankly distressing. Bent, humpy-backed, varicosed, spavined, goitred, gimpy bits of chewed gristle. They've been so abused, they should be made wards of court and given their own social workers. The owners never leave the poor things alone. They are endlessly tweaking and arranging and straightening and fluffing up. Actually, it's quite funny. Like a lot of obsessive, surface-wiping suburban housewives rearranging the front-room cushions. All keeping up with the Joneses. Do you know the difference between a heterosexual man on the beach and a homosexual man on the beach? Well, apart from the body and the back, sack and crack wax, obviously. A straight bloke walks into the sea and looks at the horizon. A gay man faces the beach. It's all about front. There is a constant scanning here. Everyone's staring and sizing up. Every time you look up, you make eye contact. 'I am an insecurity camera.' The gaydar is jammed with traffic. Even the gently frotting men in the surf look over each other's shoulders, sending out intense sonar messages. There's not much noise here. There's no laughter. Just a bit of low muttering. It's not remotely relaxed. It's not a holiday. This is a naked sales convention. Pure erotic capitalism. After an hour, Jeremy's bored. He's exhausted his game of seeing how many euphemisms for back-to-front sex he can come up with. He points up a concrete hill. 'They keep going up there in ones and twos. Why?' Well, why do you think? 'Let's go and see.' This is it. For him, this is confronting the great fear. The peek into the heart of Boy's Own darkness. This is what he came for. So we trudge up the hill. Very separately. It's uncomfortably hot. The light is neon-bright and along the cliff there are men standing or lying. Entirely on their own, like dropped bits of gay litter, waiting to be picked up. It's Hampstead Heath without the trees and wet knees. I get to the edge of a cliff and lie down. In the pale blue sea below, naked men swim lazily, looking perversely like they're in old Hitler Youth movies. About 20ft away on a flat rock, a man with a body apparently made out of knotted brown pipe cleaners and bacon rind has laid out his towel. He's wearing nothing but black leather biker boots. Now who gets up and thinks: 'Nice day for the beach - towel, suntan cream, condom, biker boots'? He hasn't even got a book. He's here all alone like some Greek-myth punishment, marooned on this rock, chained by his libido. He stares at me, then slowly turns round and bends over; sporting a pendulous scrotum, he looks like a malnourished, shaved bulldog. I look away, then glance back. He's gently masturbating at me. More for effect than intent. I can't say I'm not flattered, then I can't say that I'm interested either. Jeremy, sweaty and puffing, stumbles up. 'Have you seen... I mean, have you seen...?' He's Bill Oddie after sighting a dodo. Yes, I've seen. You need a beer. So we go back down to a little hill-top bar above the beach where a waiter in a cerise mini-sarong, matching cut-off singlet and alice band serves lager and fried octopus. I look down at the supine, oily gravel and admit that I don't like it here. I find the constant appraisal, the naked audition, the mime propositions wearying and uncomfortable. And the pitiless eugenics of homosexual coupling are depressing and sad. There is no space here for the old, the fat, the ugly or the shy. The emphasis is on a particular style of physical beauty to the complete exclusion of imperfection, intelligence, humour, flirtation or courtship. Not that these things aren't valued by gays per se: they're just not packed, along with the condoms and biker boots, and brought here. It's this little matter of zipless sex where gays and I part company. 'It's quite good here,' says Jeremy. 'I'm glad we came.' Well, that's him all over. The great contrarian. Never happier than when he's next to something he can tease and have a bit of a cathartic rant at. As I said, Jeremy's defined by what he's not. Here he's successfully confronted that last frontier - the pubescent boy's fear of homosexuality - and it's not that bad. He's not been gang-banged by the Village People. He hasn't caught a falsetto laugh or a burning desire to collect Lalique or an ear for show tunes. Best of all, they haven't asked for his autograph. He's finally found some butch blokes who blissfully couldn't care less about cars. A A Gillwww.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/public/magazine/article212465.ece#prevwww.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/public/magazine/article212465.ece#next

|

|

|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 16:24:05 GMT

Playing With Fire

They were warned. There was a significant threat of murder or kidnapping, but they wanted to see Baghdad for themselves — and found themselves in the eye of a firestormAA Gill Published: 6 November 2005 It wasn't a rocket-propelled grenade, a Sam missile or a mortar; it wasn't a bullet or even an infidel Coke bottle full of petrol that did for the helicopter. It was a bird. The aircrew showed us the splat that broke its nose. Welcome to Baghdad, where even the pigeons are suicidal. The Americans didn't have a Black Hawk to spare for the five-minute hop into the Green Zone, so we were going to have to drive it. This is the bit Jeremy swore he'd never do. When you're asked where you draw the line, this is the place to start drawing. Nobody drives into Baghdad if they've not been given a direct order. Even our minder, Wing Co Willox, has never done it. We're definitely not up for this, so we go and have coffee in the Green Bean, the American army's version of Starbucks in a Portakabin that hunkers down behind prefab blast walls, "proud to serve" skinny macchiatos in Iraq, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and any other stan that needs shock, awe and caffeine. A pair of skinny Iraqis work their way through the fast of Ramadan, serving homesick grunts airlifted blueberry muffins. An officer from the Irish Fusiliers tips up, all perky green hackle and steely Ulster confidence. "There's absolutely nothing to worry about," he says, and instantly you know there's nothing to worry about because worry is too weedy and snivelly a civvy word for what we ought to be feeling. He doesn't mention that they've just shot their way in here or that they sent an unmanned drone down the route to check it out first. We wear body armour and helmets in the car. This doesn't make you feel safer, just an oven-ready prat. Our folksy safety briefing boils down to: if by the merest chance anything worrying occurs, close your eyes, put your fingers in your ears and pretend to be a prayer mat. We travel in a small convoy. Two armour-plated Range Rovers with what they call top cover: Land Rover snatch vehicles in front and behind with a pair of soldiers sticking out the top. Being a human turret is a bad job. "We do this a bit faster than the Americans," a lance corporal tells me as we gingerly pull out of the airport perimeter. That's because the Americans do it in tanks. This road is code-named Route Irish. Guinness World Records has just authoritatively announced that Baghdad is the worst place in the world. Presumably in a photo finish with Stow-on-the-Wold. This 25-minute stretch of blasted tarmac from the airport to the Green Zone is, as Jeremy might say, the most dangerous drive — in the world. Unsurprisingly, there's not much traffic. Surprisingly, there is some. "It's relative," says the corporal. "The worst road in the world is the one the bus runs you over on. The rest are a doddle." The fusiliers drive with a practised authority, zigzagging, never contravening each other's line of fire. The top-cover soldiers swivel with their rifles to their shoulders, eyes pressed to the sights. There is a purposeful tension, a tunnel-visioned concentration. Going under bridges and flyovers is the worst: they traverse the parapets with a gaunt expectation and I begin to see everything in hyper-real detail. Every pile of rubbish and burnt-out car waits to jump out at us screaming "God is great" in a flash of hot light. The convoy slows down; not a good thing. A car ahead crawls to a stop. The soldiers emphatically signal to it to move on. Maybe it's someone taking a moment to tell God to put the kettle on; maybe it's just a clapped-out motor that's stalled. Army convoys, particularly the American and private-contractor ones, are really dangerous for Iraqis. Lethal force is everyone's first and last option. On a slip road, lopsided purposeful Toyotas packed with grim men seem to race to catch us. Perhaps they just want to get home to break their fast. Perhaps not. Baghdad looks like it's been beaten senseless, stamped on, bitten, battered and clawed; ugly and dirty, its gouged and grated walls ripped off, windows flapping, ceilings propped on floors. The thudded buildings look like rotten teeth in the receding gums of streets full of twisted flotsam, bent lampposts, tangled railings and pools of slime, all of it coated in ground concrete dust. But it also seems surprisingly familiar, like a hot estate from a suburb of Detroit or Dundee. The journey takes longer than War and Peace. So I try and think about other stuff — like what's in it for female suicide bombers? The promise of 70 adolescent virgin blokes all sniggering to give you a premature seeing-to in heaven doesn't seem like much of an incentive. And then I'm back thinking about the increasing sophistication of roadside bombs. The Land Rovers carry secret wizardry that foils radio triggers made from phones or electric car keys, but now the locals are using infrared trips and the bombs are shaped chargers, a cone lined with copper or a metal with a low melting point covered in explosives. When detonated it forms a directed stream of molten shrapnel that'll go through a battle tank. There's no armour that will protect you from being kebabbed. And then I think about the fact that the biggest helmet available fits on Jeremy's head like a little blue office-party joke hat, and that now he's facing his deepest fear (that he will cry like a girl when they video him having his head cut off with a bread knife to the soundtrack of Stairway to Heaven) looking like an unnatural cross between Obelix and the Elephant Man. The convoy gets to the first of the Green Zone's many checkpoints and the Wing Co sighs with heartfelt relief. I realise we haven't spoken a word. In the other car, apparently, Jeremy hasn't drawn breath. We deal with fear in different ways. Silently I believe that if I see everything it'll be all right. He has to say everything. The Green Zone is possibly the most bizarrely peaceful place anywhere, like the eye of a storm. It's peace is a long way from being safe. There are on average 25 serious incidents in Baghdad a day. This is when someone gets killed or their future radically reorganised — involving ramps, handrails and incontinence pads. It's an area the size of a small market town drawn around Saddam's nouveau Babylon of palaces and monuments. It has a heads-down hush, on the banks of the Tigris, amid date palms and a maze of concrete blast walls that hide government buildings, embassies, command centres, commissariat canteens, car parks and all that the gorgon's head of civil service and ordinance needed to maintain itself. The gauze of normality gives it a hallucinatory atmosphere of science fiction cut with the surreal banality of the suburbs. It's Desperate Housewives with guns. There are a lot of very neatly clipped hedges. Who's tending the privet? The strangest job in the current-affairs world must be apocalypse topiary. We turn into the British military headquarters. A garden cropped like a formation of green guardsmen, with a goat. An Abyssinian goat with droopy ears and a malevolent mien that's called either Dog or Jar Jar Binks. Where would the army be without a Sunday-roast mascot? It can only be a matter of weeks before the Mirror and the Mail are vying to save it. Maud House is named after a defunct general who passed this way in the previous century. It's instant camping English. There's tea and informality and old copies of Country Life. An air of prefect's common room. Nobody salutes or stands to attention. It's all first names, but the hierarchy is as keen as a pack of hounds. The lieutenant general who is second-in-command of this whole damn shooting match seems to spend a lot of his time half-naked, or perhaps that's half-dressed. He sports no rank badge but then he doesn't need one. Only a lieutenant general would be walking around headquarters bare to the waist. Apart from the naturism, Bims has more charm than I'd have thought possible to get into a single human being. I imagine the army has a special course for everyone over the rank of colonel that makes them devastatingly good in a room. The polite version of cone-shaped chargers. There is no defence against a blast of molten English niceness. Maud House is all shiny megalomaniac's marble, mostly bedrooms and bathrooms. It was one of Saddam's private brothels. The army, bless it, always resolutely unaware of its own symbolism, turns a politely blind eye to the fact that the Americans live in Saddam's palaces and the Brits in his knocking shop. So who's the daddy and who's the Yankie bitch? Saddam's nuclear bunker is the heart of the Green Zone. The first thud of shock and awe, dropped from 15,000ft, were bunker busters that crashed through the palace's domed roof and burrowed underground and exploded with maximum prejudice. They barely chipped the corner off the 2-billion-dollar safe box. It was built by the Germans and Swiss, who know a thing or two about vaults. One hundred and fifty people could live down here in reinforced concrete catacombs that are sprung on shock absorbers like a Posturepedic mattress. The air scrubbers and generators, the fixtures and fittings, are all looted and smashed. It smells of damp carpet and panic. There are bullet holes in the airlock doors and bloody hand prints picked out on the walls by our leaping flashlights. They look like cave paintings. For something so postmodern, this place is ultimately primitive. A cave, a shaman's secret hole in the ground. Of all the grandiose monuments that Saddam built for himself, this bunker is the most telling, with its flock wallpaper in the dining room, the gold-tapped bidets and the grim 1970s hotel lighting.  www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article153719.ece#prev www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article153719.ece#prev

|

|

|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 16:32:11 GMT

Playing With Fire (continued)  It is the most complete skin-crawling, silently screaming evocation of hell; the reinforced concrete transubstantiation of sleepless megalomania and hysterical fear. Upstairs, sunlight streams through the two holes in the dome imitating Hadrian's Pantheon. It is the most complete skin-crawling, silently screaming evocation of hell; the reinforced concrete transubstantiation of sleepless megalomania and hysterical fear. Upstairs, sunlight streams through the two holes in the dome imitating Hadrian's Pantheon.

Saddam had a Tourette's need to graffiti his initials over everything. He was a dreadful size queen. Everything's huge and pantomime-clumsy. It's always the telltale taste of the monomaniac to evoke size without any understanding of scale.

The bunker is guarded by Georgians from the Caucasus. The international nature of the force is crucial to the Americans, who shriek and swoon like the bride's mother who's trying to do a placement when some distant guest sends excuses, mucking up their arrangement of flags and the walls showing the clocks of coalition time.

The vast majority of the soldiers spend the vast majority of their time guarding each other. The truth about the army here in the Green Zone is that their biggest job is protecting themselves. The American soldiers spend a year opening and closing barriers. It's an excoriating cocktail of weeping boredom and gnawing fear. Checkpoints are magnets for suicide bombers, but the work is so repetitively stultifying that the Americans move like zombies, pressing their faces to the car windows with the uncomprehending glazed stare of guppies in an aquarium. We go to Three Head car park, named after the trio of oversized Saddam busts parked next to the tanks. Sweetly, the Americans give Jeremy and I an Abrams battle tank each. We race them between the monumental crossed scimitars at each end of the avenue commemorating the Iran-Iraq war next to the tomb of the unknown soldier, or "the who-gives-a-sh*t towel-head" as one of the grunts mutters. I ask my commander what he likes best about his tank. "Ooh," he sighs. "I suppose it's the ability to reach out and touch people."

Whatever Jeremy says, in the tank I beat him by a barrel. I always beat him. In the bright dusty sunshine we can hear the rockets and mortars land, reaching out and touching people, making someone's day. We chopper back to the airport in the mended helicopter, chugging low over the city. Baghdad is pestilent with rubbish, open streams of sewage and corruption. It's vital and virulent. From the ground someone fires at us. The old helicopter, feeling the heat, launches magnesium flares that splutter and shine like dying suns and fall to Earth in trails of white smoke.

At the camp in Basra, the night air glows an ethereal orange from the gas-burning of desert rigs. Until recently the British have had a quietly smug time compared to the Yanks in Baghdad. They've had only half an incident a day, but after we got there things went a bit Rorke's Drift.

Most of my hawkeyed reporting was reduced to watching Jeremy have his photograph taken with groups of gurning, up-thumbing crack-fighting units. It's like a military Disney World. He stands in huddles of camouflage like a big blue extra from Wallace & Gromit with a Plasticine beam and a teacup on his head.

You can't help liking British servicemen. It's the humour and the banter, the air of gawky competence, the legs-apart, four-square confidence. Our boys do a six-month tour and are trusted to have a couple of beers a day. The Yanks are drier than a desert sandbag. For many of the Brits this is the most exciting posting for years. The best thing they've ever done in their short lives. Many of them catch the old English disease of Arabism. There was a lot of optimism based, it must be said, on very little but wishful thinking and best-case scenarios, but then a war is really no place for a pessimist.

Iraqi policemen are training with Kalashnikovs — at 50 yards most of them have trouble hitting desert, let alone the targets that resemble charging Americans. I ask an instructor what they're like. He gives me a long, measured look. "Good lads, most of them, but there are cultural differences." I'm sorry, but firing a gun is the least culturally differentiated activity in the world. "It's Arab confetti, sir." And he looked at his beaming students with something short of pride. And then there are the berets. The Brits spend an obsessive and some might say risibly gay amount of time shaping and positioning their hats. The Iraqis wear them unaware. Plopped like failed soufflés.

We talk to another general, this one surprisingly overdressed, who briefs us off the record. The situation sounds winningly tickety-boo given that I only understand one sentence in 50. The well-honed military mind runs on TLAs — three-letter abbreviations. These are opaque at the best of times. If you're dyslexic, they are like alphabet spaghetti. He refers to IEDs for improvised explosive devices. I keep calling them IUDs and asking with steely, inquisitive authority why the Shi'ites are attempting to shove contraceptive devices up our warriors. And then there was the lavatory, reserved it said, for D & V, with the warning: "If you don't want it, don't use it." I imagine this was military transposition for "diseases venereal"; Jeremy works out it's diarrhoea and vomiting.

We hitch a lift in a Lynx, the sports car of military helicopters: small, agile and nippy. My feet poke out into the void. We're only held in place by a beefed-up car seat belt. Jeremy wraps the spare webbing round his hand. Here is another difference in the way we deal with fear. He likes to know hardware stuff, facts, figures, statistics. He wants muzzle velocity and metal thickness. His world is a series of engineering problems, probabilities and solutions. Nuts and bolts are his security bunny. There isn't a metaphysical cloud on his horizon. It's like being strapped in next to a why-ing four-year-old who's taken over the body of old man Steptoe.

On the other hand, I don't care a jot for any of that. It's boring and bogus. The world isn't spun by cogs, it's turned by people. I make my judgment by sizing up the pilot, the driver, the guide. If you decide to trust him, then keep up and shut up. I'd have followed the Lynx's captain any way they fancied. The chap in charge of helicopters was a marvellously urbane floppy blond Sloane from the army air corps.

A bod who was a drawling master of the military mixed metaphor "When the wheels come off you need a big punch." The soldiers called him Flasheart after the character in Blackadder. We're off to deliver a parcel to the lifeguards based in Basra.

The Lynx hurtles low, hurdling power lines, sidestepping flocks of suicide pigeons. Basra is another blasted, ugly, sewage-stained city. Every back yard a pile of rotted rubbish. Every car a cannibalised pick'n'mix. And yet most buildings boast a satellite dish pointing expectantly up at the western sky hoping to catch some good news. There isn't any. Neither is there any electricity. We fly down the canal where Saddam's yacht lies on its side, pathetically clogging the waterway. Why do dead boats look sad, but dead cars look like junk?

Then we jink off to see the Marsh Arabs. The one small, really good news story of the war on terrorism. They were persecuted to the point of extinction and their marshes drained. Now the water's back and buffalo splash through the thick reeds that are used to make delicately beautiful huts. Arabs wave from their spindly boats.

The pilot and I talk about Wilfred Thesiger and Jeremy keeps interrupting: "Who? Who?" Then we turn again to the desert and fly over the battlefield of the Iran-Iraq war. Huge areas of baked tank emplacements and trenches. From 500ft they are indistinguishable from bronze age archeology. The wreckage of ancient wars is the dusty vernacular of this, the oldest country in the world.

As we are turning back to camp, the missile snakes out at us. The Lynx spits its glowing rockets and the pilot lurches into a dive. I hang in space, watching the Earth tumble and sprint up to grab me; "300, 200, 100;" the staccato voice comes over the headset as we plummet. Thirty seconds later we're flat and level. A dot in the sky.

The machine gunner in the door says he saw the puff and the flash and the smoke chase after us. Back on the tarmac, we don't mention the missile. Jeremy does, though. For him it's personal. "I was told the Shi'ites watch Top Gear," he says in a quavering, girly voice. Well now you know — they obviously do. Back in camp we are mortared and shot at with unnerving regularity. Mortars land with a crump, like a severed head hitting a Persian carpet.

Sitting in a darkened Tristar in full body armour in the middle of the night, waiting to be flown back to Brize Norton, knowing that outside, in the oil-flared dark, helicopters quarter the desert for Sam emplacements — and the RAF regiment are manning the flight paths for 50 miles but that it will take a chest-thudding eight minutes before this ancient airliner is out of missile range — I try and think about something else. I realise that during our time in Iraq I've only spoken to one Iraqi, and that was to say: "Four mocha frappuccinos, please."

![]()

www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article153719.ece#next

|

|

|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 16:53:50 GMT

Things Can Only Get Redder

Pink cocaine, Ukrainian hookers and Gwyneth Paltrow in a crate. Jeremy Clarkson and AA Gill in MoscowAA Gill and Jeremy Clarkson Published: 28 January 2007 The flights to Moscow are full of ox-pecker businessmen. They’re all bright-eyed and bouncy with anticipation, keen to ride the rhino of Russia’s oil-and-gas boom by drip- feeding it with a selection of boutiquey Euro luxuries: shotguns, powerboats and fusion- restaurant concepts. On the way back, however, they don’t look quite so good. Bankrupted financially by Russian business practices, and morally by a Klond**esque nightlife, they are nursing empty wallets. But every single one will whisper, in a conspiratorial, blokes-only sort of way: “You can forget Amsterdam and Reykjavik. For a really good night out, you have to get yourself to Moscow.” So that’s what Adrian and I did. Actually, that’s not strictly true. I wanted a good night out. I wanted to eat my supper from the toned belly of a Ukrainian hooker while snorting pink cocaine from the back of a golden swan. Adrian, on the other hand, wanted to queue for bread, and beat himself with twigs while sampling the workers’ struggle for control of the factories. Before leaving, therefore, he fixed a translator who was an artist and would show him some of the struggle, while I called the people from Russia’s Top Gear magazine, who knew some people who might be able to help with the swan and the naked Ukrainian. So, at the airport Adrian was met by his rather dreamy translator in a smashed-up taxi, and I was met by a Maybach. Also, there was a Cadillac Escalade full of policemen in paramilitary uniforms, sub-machineguns and a selection of potato-faced meat machines who talked into their cuffs a lot. Adrian looked at the taxi and the dreamy translator. And he had a struggle for, oooh, about one second, deciding whether to go with them or get in the creamy Maybach with me. It, and the sub-machineguns, all belonged to a businessman we shall call Matthew, and at first I thought it might be a bit of an ego trip. I mean, he publishes magazines and makes fountain pens. But this meat-’n’-metal protection was not for show. Three years ago, Matthew was kidnapped by Chechen terrorists. He was beaten, handcuffed to a former special-forces soldier, blindfolded and taken to a flat somewhere in the uniformly grey, monolithic, high-rise outskirts of Moscow. The Chechens called his father, who lives in Spain, saying that unless they received $50m within five days, the boy would be killed. His father roared back: “$50m? F**k off!” And with that he turned off his mobile. For two days. Matthew waited five days for his kidnappers to drop their guard and then leapt out of a fifth-floor window. It’s hard to say what shattered his legs – the impact, or the bullets fired by the guards as he fell. But whatever, he crawled to a nearby road, flagged down a passing motorist, and over the next seven months watched the entire gang being sent to prison, where, he says quietly, all of them met with accidents and died.  www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article57126.ece#page-1 www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article57126.ece#page-1 |

|

|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 17:07:27 GMT

Things Can Only Get Redder (cont.) I liked Matthew enormously. And here’s something truly amazing. Adrian, who dislikes people until he gets to know them – and then dislikes them even more – liked him enormously too. Partly, I suspect, because Matthew could get us into restaurants.He suggested Pushkin, where Clinton and Kofi Annan eat when they’re in town. It served borscht but other dishes too. I wanted to savour it all, since everything cost a billion, but Adrian was in a hurry. He’d wangled an invite to a special party and had a surprise for me.So did Matthew. To get us to the party, we had the Maybach, of course, and the Cadillac meat-wagon, but now we had a Lamborghini as well.Our convoy sent the security at the party into a complete tizzy. Their meat and our meat rushed about speaking into their cuffs and tapping their ears, and pretty soon we were inside a room of pulsating sweat and testosterone.We were ushered through the outer zone, past girls of such ravishing beauty that I barely noticed most were pretty much naked, into the VIP enclosure, which was full to bursting with photographers. All were crowded round a large wooden crate where, plainly, something big was happening. Adrian assured me that this was my surprise, and after he’d pushed me to the front he almost said: “Da-daaaa!”It was Gwyneth Paltrow, sitting in the crate on a roped-off bar stool, all on her own. Quite what she was doing there I have no idea, because as I drew breath to ask, the photographers turned their attention on me. Not even my meat was big enough to deal with the onslaught, so we put our heads down and, leaving Gwyneth in her big box, barged our way back to the cars.On our way to the next party – the opening of a restaurant, I think, for girls at least 7ft tall – we saw the first of many car crashes. Crashing, it turns out, is something the Muscovites do a lot.In Soviet days, you could have a flashing light on your car if you were connected in some way to government. And this is still the case. Tax inspectors. Lollipop ladies. Men from the ministry of fish. They all have what they call “blinker cars”.But now, for $500, anyone can buy a licence to have a blinker car. This means that at every road junction, almost everyone has the right of way, and Moscow echoes almost permanently to the sound of tinkling glass and tortured metal.We steered through it all and made it to the party, where I assumed, from the massed ranks of tanned and elongated flesh, that my Ukrainian hookers had turned up. Sadly not. They were just girls out on the town, trying to hook up with an oligarch. This counted Adrian out. In fact, he claimed he was starting to feel like Madge, so soon we were back in the Lambo-bach-illac convoy for a sprint over to a lap-dancing bar. So there you are. The Russian night out. Expensive girls. Expensive food. And a dirty great Lamborghini. The only difference with London is that your wife’s at home.If I’m honest, Adrian spent most of the night looking like something heavy had landed on his foot, and I spent most of the night talking to a girl in our party whose grandfather, Vladimir Chelomei, had been made a hero of the Soviet Union for inventing what became known as “Satan”: the SS-18 intercontinental ballistic missile. For more than 20 years, this was the launch vehicle for Russia’s nukes. For a generation, it brought sleeplessness and terror to 500m people in the West. Me included. Yet here I was, sitting in a bar full of naked Ukrainian ironing boards, chatting to its inventor’s agreeable granddaughter. Tell me the world is not a weird place. I dare you. I double-dare you.So where was Madge going to find his struggle? “In an art gallery,” he said with the grin of a maniac.Apart from seeing what would happen if I relieved myself on Lenin’s tomb, I couldn’t think of anything I wanted to do less. So we did a deal. “If you can name a single Russian artist, we’ll go.” He couldn’t. So we didn’t. I liked Matthew enormously. And here’s something truly amazing. Adrian, who dislikes people until he gets to know them – and then dislikes them even more – liked him enormously too. Partly, I suspect, because Matthew could get us into restaurants.He suggested Pushkin, where Clinton and Kofi Annan eat when they’re in town. It served borscht but other dishes too. I wanted to savour it all, since everything cost a billion, but Adrian was in a hurry. He’d wangled an invite to a special party and had a surprise for me.So did Matthew. To get us to the party, we had the Maybach, of course, and the Cadillac meat-wagon, but now we had a Lamborghini as well.Our convoy sent the security at the party into a complete tizzy. Their meat and our meat rushed about speaking into their cuffs and tapping their ears, and pretty soon we were inside a room of pulsating sweat and testosterone.We were ushered through the outer zone, past girls of such ravishing beauty that I barely noticed most were pretty much naked, into the VIP enclosure, which was full to bursting with photographers. All were crowded round a large wooden crate where, plainly, something big was happening. Adrian assured me that this was my surprise, and after he’d pushed me to the front he almost said: “Da-daaaa!”It was Gwyneth Paltrow, sitting in the crate on a roped-off bar stool, all on her own. Quite what she was doing there I have no idea, because as I drew breath to ask, the photographers turned their attention on me. Not even my meat was big enough to deal with the onslaught, so we put our heads down and, leaving Gwyneth in her big box, barged our way back to the cars.On our way to the next party – the opening of a restaurant, I think, for girls at least 7ft tall – we saw the first of many car crashes. Crashing, it turns out, is something the Muscovites do a lot.In Soviet days, you could have a flashing light on your car if you were connected in some way to government. And this is still the case. Tax inspectors. Lollipop ladies. Men from the ministry of fish. They all have what they call “blinker cars”.But now, for $500, anyone can buy a licence to have a blinker car. This means that at every road junction, almost everyone has the right of way, and Moscow echoes almost permanently to the sound of tinkling glass and tortured metal.We steered through it all and made it to the party, where I assumed, from the massed ranks of tanned and elongated flesh, that my Ukrainian hookers had turned up. Sadly not. They were just girls out on the town, trying to hook up with an oligarch. This counted Adrian out. In fact, he claimed he was starting to feel like Madge, so soon we were back in the Lambo-bach-illac convoy for a sprint over to a lap-dancing bar. So there you are. The Russian night out. Expensive girls. Expensive food. And a dirty great Lamborghini. The only difference with London is that your wife’s at home.If I’m honest, Adrian spent most of the night looking like something heavy had landed on his foot, and I spent most of the night talking to a girl in our party whose grandfather, Vladimir Chelomei, had been made a hero of the Soviet Union for inventing what became known as “Satan”: the SS-18 intercontinental ballistic missile. For more than 20 years, this was the launch vehicle for Russia’s nukes. For a generation, it brought sleeplessness and terror to 500m people in the West. Me included. Yet here I was, sitting in a bar full of naked Ukrainian ironing boards, chatting to its inventor’s agreeable granddaughter. Tell me the world is not a weird place. I dare you. I double-dare you.So where was Madge going to find his struggle? “In an art gallery,” he said with the grin of a maniac.Apart from seeing what would happen if I relieved myself on Lenin’s tomb, I couldn’t think of anything I wanted to do less. So we did a deal. “If you can name a single Russian artist, we’ll go.” He couldn’t. So we didn’t. www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article57126.ece#page-2 www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article57126.ece#page-2

|

|

|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 17:14:30 GMT

Things Can Only Get Redder (cont.)  I’m not saying Moscow can’t stun you, though. I’ve seen two views in my life that have genuinely taken my breath away – Cape Wrath and Hong Kong at dusk. And now a third. Red Square. We came at it from the south, through the new arch by the Museum of Something Not Interesting. And even though a portion of the cobbled centre was taken up by a makeshift ice rink, the rest was so beautiful and so evocative I actually gasped: St Basil’s, the silly onion-shaped church whose designers were blinded after they’d finished it to make sure they never did any such thing again; the blue fir trees that are replaced quietly, and overnight, when they grow taller than the placenta-red Kremlin walls they shield; and the big department store lit up like Harrods. You find yourself whizzing round and round like an eight-year-old in a shop full of train sets, not quite believing that an image you’ve seen a million times in pictures could be so much more eye-wateringly spectacular in real life. Best square in the world? Oh yes, and by quite a margin. Later, in a market where you could buy cheese made from a Bolshevik’s armpit sweat, there was a kerfuffle. A man had stepped forward with a pen and paper to ask for my autograph, but long before he could utter a sound, my meat had pulled his arm off. The pen and paper were examined, and when both were discovered to be harmless, the man was allowed to proceed with his request. Which he did without a trace of indignation. For the most part the centre of Moscow looks like London. You really can see that the two cities were joined at the hip before everything went tits-up in 1917: the same architecture, the same sense of history, the same retail experiences, and the same silly six-figure restaurants. I’ve never been so far and felt quite so at home. What’s more, just as though we’d been in London, Madge failed to find much struggle and I never got to dip a quail’s egg into a Ukrainian teenager. We had a nice time in what appears on the surface to be a nice place. There’s nothing to indicate that you’re in a 21st-century Wild West. Even the guard at Lenin’s tomb was smoking a fag like he wouldn’t have cared if I’d weed on it. Or him. And yet the autograph-hunter seemed to demonstrate that there is an inbuilt fear of muscle and authority. You don’t question anyone with more money or biceps or contacts than you. The price of asking for an autograph is a severed arm. The cost of a speeding ticket is a quiet bribe. You get the best table in the house with a small glare. We saw this, too, on our run back to the airport, when we were given a police escort. Blue lights flashing, we tore down those special lanes reserved in England for buses, but in Moscow for the rich and powerful. After Plod had barged slower traffic out of our path on the motorway, we swept straight up to the VIP lounge, breathless with a mix of cheek-reddening embarrassment and butterfly-tummy excitement. Then, after we’d thanked our meat for murdering the autograph-hunters, and waved a tearful goodbye to the Maybach, we found ourselves on the plane, back in the clutches of a real democracy. In economy class. I prefer theirs.   www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article57126.ece#next www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article57126.ece#next

|

|

|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 17:42:19 GMT

Watford Minds the Polling Gap

The Hertfordshire town is that rare thing: a three-way marginal that all the main parties stand a chance of winning

AA Gill and Jeremy Clarkson Published: 25 April 2010

Watford doesn’t exist. I know. I’ve been there. Watford is the word for the little offcuts of the world, the edges of things that have no real purpose like the bits of gravel under motorway flyovers and the gaps between houses where you put the bins. It is barely famous for only two things that aren’t in Watford: the gap, which is in Northamptonshire, and north of Watford, the aesthetic and cultural boundary above which people eat their tea for dinner and their dinner for lunch, and beneath which they don’t wear socks in bed and aloof is not the ceiling of a Chinese takeaway. Watford’s parliamentary constituency is a three-way contest. There are only 2,000 people between the three candidates and it’s both a Liberal Democrat and Tory target seat. It’s half commuter and half local light industry and they’ve got a lot of transient Poles. It could be Watsaw. There are also more than 50 places of worship, which may seem a little outré unless you have actually been here and then you’d realise that the need for belief in a better afterlife is pressing. It’s twinned with Limbo. Mindful of the hard time I’ve been having getting politicians actually to talk to me, I took along Jeremy Clarkson. It is a fact that everyone in the world wants to talk to Jeremy. With a single call, every candidate said: “Yes please. When? Where? And how high?” Clarkson is like the Inquisition: nobody expects him. The sight of Jeremy on the peeved streets of Watford is akin to finding a Yeti in your bath — and not dissimilar. Cars swerve, tracksuited larrikins crash their stunt bikes into street furniture, the unemployed do the green cross code of celebrity: look once, look twice, look once again. And occasionally, overcome, they shout ecstatically: “Clarkson! God! Yes!” As we got out of Jeremy’s unbelievably expensive and ferociously rare Mercedes, a middle-aged chap, stunned, said: “Oh my God, you’re AA Gill. I haven’t seen you since the premiere of Witches of Eastwick — the Musical.” It turns out he was married to Cameron Mackintosh’s boyfriend’s auntie. What are the odds of finding the one show queen in Hertfordshire? We started with the Lib Dems, who had their office in an industrial estate beside a mail-order sex equipment warehouse. The Liberals were outside to meet us. Perhaps it was the proximity of so many dildos but I couldn’t help noticing they all had comfortably vast bottoms. See how many times you can mention arses, I said to Jeremy. He got in a bottom line, a bum deal, expenses booty; I managed only three fundamentallys and a sod. In the back of the office they have a small factory printing leaflets, newspapers, letters — begging and threatening — and possibly banknotes and photo registration. They suggest we go canvassing to a silent Watford housewives’ street. It screams with suburban despair, a living museum of Tudorbethan pebble dash. Terry Scott and Barbara Amiel were both born in Watford. I’m pretty sure that’s the first time they have appeared in the same sentence, but there is something of both in this place. I realise no one with a camellia is ever going to vote Labour. The people without camellias have fresh-looking Lib Dem boards. “What are we doing?” whispers Jeremy. Well, it’s a bit like selling tea towels and ironing board covers door to door, but they’re flogging Clegg and Cable. It’s a displacement activity: it makes them feel this is personal, but no one does it at 11am, because everyone’s out, especially if you’re in a commuter non-town. They did find an Indian couple and an African woman with a baby and a pair of Chinese computer programmers. If we’d had an Eskimo and a bipolar dwarf, we’d have got the complete set. We’re being played, I told Jeremy. Then a handsome, tousled couple wearing bits of each other’s pyjamas and bare feet, ran into the street to tell Jeremy he was amazing and have their photos taken. “You’ve actually just got out of bed, haven’t you?” The girl smirked. That’s Clarkson interruptus. The candidate, Sal Brinton, is a square woman of formidable dimensions who has come out in the same turquoise jacket as her agent. (There will be words.) The agent tells me with a solemn intensity that the candidate’s CV is really really impressive, as if it were the Rosetta Stone. Sal says she wants to talk local issues. That includes a lot of gossip and innuendo about other candidates and she assures us with a completely straight face that this is a two-horse race, Liberals versus Labour. The Tories aren’t registering at all. And here’s the thing with the Liberals. For all their otherworldly, decent self-promotion, for all their CVs, if they really want their constituency they are Dick Dastardly at the Wacky Politics. They play dirty. They call it “pulling out all the stops”. Next it’s Claire Ward, the sitting Labour MP. We find her in a shopping street standing next to Jack Straw, the justice secretary. As if things weren’t bad enough. They’ve attracted a small crowd and Straw is taking questions. There’s a soldier in desert camouflage, a little knot of Islamic brothers, a lot of the newly unemployed. Straw answers with that familiar, blinking, thoughtful but halting manner. I watch a secret policeman in dark glasses play grandmother’s footsteps with a man in kurta pajama with a beard and a plastic bag. Jeremy stands in the middle of the crowd like an incognito Chewbacca. The last question is: “Mr Straw, would you take away Jeremy Clarkson’s licence?” The justice minister chuckles. We all chuckle. Jeremy stands in the middle of the crowd like an incognito Chewbacca Straw comes over and says: “There’s nothing like this. Nothing like soapbox politics. I love talking with people. I do it all the time in Blackburn. All the time. Marvellous.” He’s standing with a radio mike, whistling in the wind. We talk to Ward in a coffee shop. She’s quiet and sanguine in her tight red suit. She hasn’t exactly given up, but she’s handing out the last rounds of ammunition to her two helpers. Her agent keeps repeating: “It’ll be a personal vote if she wins.” All too often you don’t get to see the true nature or value of politicians until they’re staring defeat in the bottom. Ward was the youngest of the Blair babes; her departure will mark the end of the shallow and vain experiment that was new Labour, that wasted so much talent. Finally, we find the Tory, Richard Harrington. He’s manning a trestle table outside an empty shop with a team of bright young helpers. The Tories have been most reluctant to ditch their traditional stereotypes: everyone here is being played by Harry Enfield. The Labour party doesn’t hang about in donkey jackets and flat caps with whippets and consumption any more. We take Harrington to lunch. He’s wearing a Lib Dem bottom as a stomach and orders multiple plates of Italian food. I know that he’s talking and saying perfectly sensible one nation Disraeli-ish things. I know he’s concerned with all the souls in his constituency, including the Poles. I know he’s said that politics is his second midlife crisis and I wonder why he doesn’t just buy a Mercedes like everyone else. He and Jeremy chat, but I tune out and mesmerise at his ability to shift food. Not eat so much as inhale vast quantities. He’s like some agricultural process. I’d guess he’s eating emotions. That food is a palliative. As we leave, Jeremy has stopped by the 500th kid who wants a photograph and he says: “You had one of your turns, there. Just switched off. What’s the matter?” Well, I was just wondering. Do you think that putting cameras in phones was the worst thing that ever happened to celebrity? And there’s something else. I don’t think Harrington’s quite right. “What do you mean?” Well, you know he had marinara, spaghetti with seafood? Well, had them put parmesan on it. And then a cappuccino. “So?” Well, you never ever put cheese on fish pasta. “Oh good grief. You think I’m funny about cars.” Well, you are. (PS: 50,000 people signed a “Make Jeremy Clarkson PM” petition. The people who signed “Don’t Ever Make Jeremy Clarkson PM?” 87.) www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/Election/article272515.ece#page-1

|

|

|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 17:50:24 GMT

Watford Minds the Polling Gap (cont) Liberal Democrat candidate Sal Brinton (Jeremy Young) Liberal Democrat candidate Sal Brinton (Jeremy Young)

The journey to Watford was very terrible. I had told Adrian Gill that I’d never been on the campaign trail before, so he decided to explain how it works: “There are three main parties and they contest seats. The winner is the one . . .” It was like setting out on a dreary school field trip with the worst teacher in the world. And the only reward is that eventually I arrived in Watford. On the surface it is much like any British town. The centre is all angles and glass and bits of sick from last Saturday night. And the outskirts are made up of kebab shops, Poles, pizza joints, Chinese takeaways, police helicopters and more kebab shops. But there is one important difference. The pawn shop in Watford is full of electrical appliances and power tools. But, unusually for such an establishment, there were no diamond rings. According to the shop’s manager, this is because they are unsellable. So the gold is melted down, the owner gets maybe 20 quid — “enough for a KFC supper” — and the diamonds are thrown in the bin. The bin? “Yes, the bin. We just throw them away.” You would imagine, then, that any town that views diamonds as landfill is likely to be a Tory stronghold. Not so. It’s a Labour marginal. Or it was, until Nick Clegg flashed his winning smile on television and the whole nation rose up as one and declared. “Yes! We are fed up with Labour and Tory. We will vote instead for the pillow-biters.” At the bustling Lib Dem HQ, the anti-nuke peace-on-earth dog-murderers have a Toyota Prius parked outside. I don’t think the people working there liked me very much. One announced, apropos of nothing at all, that he doesn’t much care for my television programme, then thrust a leaflet into my hand with such venom that it got all crumpled up. Happily, the mood was lifted by Mr Gill, my teacher, who decided to deliver one of his lectures. “The thing is,” he said, “I think you may have exceeded your spending limits. I notice here, for example, that your election leaflets were printed in London E6. . .” Quite what this had to do with anything, none of us quite knew. So after a bit of a pause, Sal Brinton, the candidate, suggested that we accompany her on a spot of door-to-door canvassing. We followed her Prius — sometimes, I couldn’t help noticing, slightly above the speed limit — to a part of the town where the gardens were tidy and there were many panes of bullseye glass. As sure a sign as a shot dog that you’re in pillow-biter territory. As her team set to work, Brinton was adamant that we hadn’t simply been taken to a zone where all the fire was friendly. Hmmm. The first woman to come along bounded up to the candidate with a cheery “Hi, Sal”. And then, noticing that we were there, followed it up with a hesitant “Er ... nice to meet you.” Everyone who came out to chat said that they would be voting Lib Dem. And almost without exception they said that their decision had been based on Clegg’s winning smile. Lib Dem policies? No one I met all morning could name a single one. This was my first experience of canvassing and it all seemed completely pointless. Because let’s just say Brinton wins. That will be down entirely to a television programme, not her endeavours. And what’s her reward? Well, a lot of commuting, weekends full of stupid people coming to surgery to make a nuisance of themselves and a team of eight-year-olds deciding every day on what her opinion should be on everything. Claire Ward, the Labour candidate, listened to this theory with the resigned expression of a seasoned campaigner. She knows. She was just 24 when she took office, the youngest female MP. And she’s been there for 13 years. We listened with her to Jack Straw taking questions from passers-by. He was good at it. It was a nice day, there was a lot of blossom on the trees and standing there listening to a politician getting grilled by voters: it was like having warm milk dripped into my ears. Just for a moment I thought we might actually be living in a democracy. Over a cup of coffee Ward told us that in the olden days an MP going to his constituency was greeted off the train with a brass band. Now it’s rather different. True enough. They couldn’t be viewed with more suspicion if they ran down the high street, naked, with an axe. Perhaps that’s why, in our time with her, Ward didn’t do any campaigning at all. Not even Lib Dem pretend campaigning. She just drank coffee. I asked if she would advise a teenager to go into politics these days, when power comes from Peter Mandelsthingy’s inner circle, the cabinet’s a rubber stamp and everyone else is lobby fodder. She paused for the longest time and then just as she was drawing breath to speak, Mr Gill from the Lower Fourth piped up: “Clarkson, do you know where the expression ‘whips’ comes from? Do you? Do you? Come on boy. Answer.” Yes, sir. Whipping-in. Hunting. Poor old Ward looked a bit bemused. She wanted to talk about Top Gear. She had been to a studio recording and liked it very much. She has a nice old V8 Jag. I think she’s going to lose. I think she thinks she’s going to lose. Pity. The Tory candidate is very fat. He’s called Richard Harrington, he’s 52, he drives a Honda Civic and after a life in property he has now decided to try his hand at standing outside a closed-down shop in Watford High Street, telling old ladies that David Cameron will mend their eyes. He suggested we had lunch. A big one. He ate lots but despite this he never let up for a minute. There were many things that made Harrington mad and all of them were Gordon Brown. He wants the Scotchman out and sees it as his job to shepherd the people of Watford into helping him fulfil that dream. Local issues? Yes. But only once Brown is gone. Bloody Brown. Bloody financial meltdown. Bloody Brown’s fault. It was like being at every dinner party I’ve been to in the past two years. Watford is twinned with Novgorod, but Harrington is twinned with Phil Spector, only with less murdering. It was great because, thanks to the wall of sound, Mr Gill was unable to get a word in edgeways. I fear, though, that all the cajoling and all the passion and all the Jack Straw is pointless. The newspapers, the radio and the television are all full of the election. What politicians say, what they do and how they hold their hands: it’s all analysed in minute detail. Did they cock up? Did they contradict themselves? And over now to a specially extended edition of Question Time. It’s massive overkill. As we were leaving Watford, I asked a young girl in the street which way she would be voting. She said she didn’t think she could vote because she thought she was too young. She was 18. www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/Election/article272515.ece#page-3www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/Election/article272515.ece#page-4

|

|

|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 19:42:41 GMT

Are We Stuck?

We put Clarkson and AA Gill on a boat in France in the hope that at least one would fall in. What happened was even worse… they fell in love with France

Jeremy Clarkson and AA Gill Published: 1 July 2012 AA Gill and Jeremy Clarkson clashed over their views on the French (Lorena Ros)AA Gill AA Gill and Jeremy Clarkson clashed over their views on the French (Lorena Ros)AA Gill

Of all of Clarkson’s ruddy, intransigently stubborn, pouty, Yorkshire-contrarian beliefs, hunches and prejudices, perhaps the most obtuse and unbelievably counter-intuitive is his deep, soulful love for the French. You would laid good money on the fact that Jeremy would be an arch frog-botherer, that he’d have a Falstaffian loathing for the cringing, beret-wearing, philosophy-spouting, bike-pedalling, arrogant French. He’d be mocking their Napoleon complexes and flicking Agincourt V-signs from the Eurostar. But non, mon brave. He admires the French above all of God’s creation. He says he likes their attitude, their style of life, their priorities, their dress sense, their undress sense, their flirtatious insouciance, the way they smell, the way they eat small birds under napkins, and the way they drink their wine. But mostly what he adores about the French is that they have never heard of Jeremy Clarkson. Jeremy’s love of the French is unrequited. And that’s the way he likes it. He can wander round without people stopping him to share a photo, or ask why he doesn’t like Peugeots, or just to shout: “Mon dieu, mon dieu, zut alors, c’est motorbouche!”

He is explaining all this to me in the garden of a restaurant in Carcassonne, while we’re having our photograph taken. “Look around you and sigh,” he says expansively, waving his glass at the fig trees, the battlements and the remains of the cassoulet. A passing Frenchman pauses to watch and asks if this is someone famous. He looks again and suddenly recognises the big fella. “Mais bien sûr! Eet ees Tom Jones.”I, on the other hand, take a more orthodox view of the French. Like you, I think they are ridiculous, self-absorbed, cultural prigs who are breathtakingly selfish and dismissive, and suffer an inferiority complex that they cover up with bombast, boasting, Olympic sulking and baroque mendacity. In France, telling the truth is the sign of a boorish lack of intelligence and imagination. So, here we are in the Midi. Jeremy — or Tom, as I shall now always know him — has come to show me why I should love them, while I trust that a weekend will convince him they are as adorable as their pop music. Carcassonne is a good place to start. Jeremy points to its ancient beauty; the old roses draped across pale stone, the gravel, that particular hoity élan with which the French move through the world, the over-coiffed ladies with too many rings on their lardy fingers, the young lovers with their wandering hands. The sky is pale blue, there are sparrows, and it’s beguiling. But it’s French, so not what it appears. There is, as they say, beneath the paint and the perfume, the scent of merde. This crenellated hill town where they shot the film Robin Hood is a lie. It’s a modern tourist’s recreation. The French destroyed the original themselves. This bit of the country was host to one of the worst pogroms in Europe — one of the few times a power has managed to exterminate an entire religion. The Cathars were a Christian sect notable for their pacifism and abstinence. French Catholics saw this as an unforgivable heresy, and set about killing all of them. The cardinal in charge of the cleansing was asked how the besieging soldiers should tell the difference between a heretic and a Catholic. He replied: “Kill them all. God will know his own.” The French are surprisingly bad at history, although it’s perhaps not so surprising when you consider how often they come second in it. Unable to beat anyone else in Europe, the French regularly turn round to beat each other. The Cathars, the Huguenots, the Terror, Vichy, Algeria. There is a torture museum in Carcassonne, a lot of tableaux of Nylon-wigged shop dummies being eviscerated, hanged, stretched and intimately ravaged, in a display that manages to be tackily sadistic and embarrassingly erotic. We are to take a boat down the Canal du Midi. Tom says he’s wanted to do this all his life. “I will,” he says, “be rendered speechless by the unfolding diorama of bosky French perfection.” Or words to that effect. We tip up at a hot marina, full of white plastic pleasure boats that look like bathroom fittings on steroids. We are shown the ropes by a friendly and efficient Cornishman, who sailed through here and decided to stay. Tom tells him to ignore me, because I won’t understand anything, and then says he doesn’t need to be told anything because he already understands everything, but is there a TV for the grand prix? There is. We cast off, or slip anchor, or whatever the nautical term for “mirror, indicate, move” is. The boat is really an idiot-proof wet dodgem with two cabins, dodgy plumbing and lots of rope. We fill the fridge with rosé and salami and olives, and Tom Pugwash gets in the captain’s chair with a pint of wine, 40 tabs, a plate of sausage, and open water ahead of him. I must say, I’ve never seen him so happy. I suggest he puts on suncream, because his bald patch is turning the colour of a Zouave’s trousers. “Do I look like a homosexual?” he shouts gaily. No, not even a Frenchman could mistake Clarkson for a practitioner of le vice Anglais. The boat is very slow. But too soon, we approach a series of locks and a happily lethargic Pugwash turns into Captain Bligh, bellowing at me to do things with ropes and bollards while explaining the principles of lockishness. I’m not comfortable doing matelot stuff, I come over all Nelson when confronted with knots. But Tom howls and gesticulates, the boat jostles and butts the groin. Locks may be triumphs of Archimedean engineering, but they’re a terrible bore. Why can’t there be a ramp, or a lift? The French lock-keepers all have jobs for life, and behave like it. They also have pleasant cottages and little businesses on the side, selling gardening gloves to soft-handed English people with third-degree rope burns. They take an hour and a half for lunch every day, from 12.30. It would be entirely possible to come on holiday to the Canal du Midi and spend all of it bobbing in a queue waiting for a Frenchman to finish his baguette and tup his neighbour’s wife. We stop off for lunch in tastefully picturesque little towns. French public holidays are arriving like locks at this time of year, and your froggy workman takes what they call “the bridge” ( le pont); that is, they make an extra holiday out of the loose days between holidays. So pretty much the only people who are open for business are English. And jolly good they are at it too; the best food we ate here was made by a couple from the Midlands. The excellence of French bourgeois cooking is now as rare as Cathars. One evening we sat outside a cafe in a typically French square, where a French pop group was tuning up. At the other tables, families drank wine and ate a late dinner of steak and frites. “Look at this, just look at this,” says Tom. “You can’t pretend you don’t want to live here for ever and ever.” We’d already been beaten to it. The locals all turned out to be from Rotherham, and waved at Jeremy and took pictures and asked what he thought of Peugeots. Apparently, most of the town is now owned by expats, happy to exploit the locals’ sophisticated reluctance to work. The band struck up Smoke on the Water. Tom beamed and played air guitar. There is no denying the canal is beautiful. Now bereft of practical purpose, it has settled into being a metaphor, a parable. Pootling down it past the arching beams of the plane trees is possibly the most relaxing thing I’ve ever done. There is something about the glossy water, the slow perambulation, the rhythm of the passing trees, the birds singing, the dappling, piebald light. You could feel the care fall away, your shoulders slump, the brain cease to race. It is, I expect, what dying’s like. When you hear the faint voices calling, “Go toward the light, granddad, don’t fight it,” I expect this is what you’ll see. I hope death comes to us like floating down the Canal du Midi. Through the tree trunks you could see the fields, running to the hills in the distance. They are thistle-bound and choked with weed. It looks so peaceful because it’s moribund, comatose. France, with its huge state, its insincere smile, its polished manners, is rotting like a pear from the inside out. There is one more thing we have to do. Jeremy wants to play a game of pétanque. We find a gravel pitch and he says: “Now, I’ve got to tell you, I’m very good at this.” Jeremy is very, very competitive. Over the years, he and I have played golf in Cheshire, raced Ski-Doos in Iceland, jet skis in Barbados, fired Kalashnikovs in Basra, and raced battletanks in Baghdad. I’ve won every time. Except for golf, which was abandoned due to helpless laughter. Boules was Jeremy’s game, on his adopted home pitch, and despite appalling gamesmanship and outright fouling, it was Agincourt and Waterloo all over again. Tom Jones, nul points. AA Gill's sketchbook Gill may have failed to conquer the French canal lock system, but he has succeeded in capturing his travel partner’s likeness in this sketch entitled; 'Sunburned Clarkson on the Canal'  During the sparring duo's trip, AA Gill found time to sketch his surrounds. This picture shows a girl reading with her bicycle on the left bank of the canal  This sketch captioned as ‘The boy who didn't recognise Jeremy Clarkson’, recalls a memorable moment in Carcassonne  AA Gill captures the calm expanse of the Canal du Midi in this sketch, captioned as ‘The View Before You Die’  AA Gill expresses his new found admiration for France in this colourful sketch www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/Magazine/Features/article1068338.ece#page-1

|

|

|

|

Post by RedMoon11 on Jul 27, 2014 19:56:19 GMT

Are We Stuck? (cont) Gill finds English staples in a French supermarket (Lorena Ros)Jeremy Clarkson Gill finds English staples in a French supermarket (Lorena Ros)Jeremy Clarkson